Yardsticks for CitiesThe first chapter in Part I of Carfree Cities.

|

|

We begin with techniques of measurement. Here at the naval shipyard in Venice, the meter and the passo Veneto have been cast in bronze and bolted to the wall for ready reference.

|

|

YARDSTICKS FOR CITIESThe first part of this chapter defines a number of measures that indicate how well a city performs its function as the host for civilization. The second part applies these measures to two extreme urban forms: auto-centric Los Angeles and carfree Venice. |

|

|

|

Quality-of-Life Measures

|

|

Except for air pollution, the range of variation on these measures will be relatively small among cities in rich nations. To these statistical measures of quality of life, we must add one quality that is difficult to quantify: the prevalence of neighborhoods built on a human scale to serve human needs. Such neighborhoods are usually characterized by the following attributes:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Transport MeasuresTravel Time

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Suburban sprawl is typified by the US pattern of postwar development. Single-family houses are built on large lots. Nonresidential functions are located in specialized districts, far from home. |

Car drivers usually escape walking, waiting, and transferring, but in many urban areas these savings are overbalanced by the effects of suburban sprawl, which forces people to:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Central Artery project in Boston will bury 257 lane-kilometers of highway costing $10.6 billion and will provide capacity for 190,000 cars each day, so the capital cost per daily car is $55,000.

http://www.bigdig.com

|

Land Consumed by Transport |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The American Automobile Association estimates the direct costs of a mid-sized car at $4504/year.

from “Transportation Cost Analysis”

Victoria Transport Policy Institute http://www.vtpi.org/tcasum.htm |

Direct Costs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Most urban rail systems charge a flat rate per trip, but some systems charge fares based on distance. Of course, if a passenger buys a season ticket, his entire cost is periodic and unaffected by usage. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proposals have been made to charge for insurance on a per-mile rather than a per-year basis, in order to discourage driving and charge drivers for their actual risk exposure. | Passengers usually pay at least some of the direct costs, but governments often subsidize much of the remainder. (In the USA, virtually every passenger transport mode is subsidized, directly or indirectly.) Most car drivers underestimate the out-of-pocket cost of driving and are unaware of the large subsidy they receive. Drivers tend to equate their costs of driving to the cost of gasoline consumed plus parking and tolls, but the driver actually pays much more than this: depreciation and maintenance are large costs that are not paid at the time of travel, so drivers are not particularly aware of them. The system is arranged in such a way that, once you have a car, the cost of driving additional distance seems fairly low, which tends to encourage more driving. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Externalized Costs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The Yardsticks AppliedEach page contrasts one aspect of life in both cities, taking first Los Angeles and then Venice. For each city, the influence of transport on that aspect of life is taken up first, followed by the consequences for quality of life in that city. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Some reviewers held such a comparison to be unfair, and while this criticism may be accurate, it misses the point. The comparison merely highlights the extreme deterioration of public spaces characteristic of auto-centric cities and shows that repulsive public areas are not intrinsic to modern life. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The ugliness of Los Angeles stems quite directly from its auto-centric patterns. Other factors less germane to the subject of this book, such as the globalization of the world economy and the rise of multinational corporations, surely also affect Los Angeles. It is worth noting, however, that both McDonalds and international package express companies found ways to adapt their normal methods of operation to the unique requirements of Venice. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Indeed, the Fenice opera house, one of the jewels of Venice, was devastated by fire a few years ago, but the building will be completely restored. All of the necessary skills and materials are still available. |

Even though Venice is centuries old, nothing in Venice could not be replicated today: there are no technical barriers to the construction of new cities just like Venice. Doubtless, some aspects of Venetian construction would be seen as prohibitively expensive today, but the large majority of buildings in Venice are actually quite ordinary and require nothing more difficult or expensive than a modest amount of stone-cutting of a type still commonly seen in new and reconstructed buildings throughout southern Europe. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This chapter concludes with a tabular comparison of Los Angeles, Venice, and the carfree city as proposed in Part II. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

No place to play |

Where Do the Children Play?The constant travel within the confines of a car delays the exposure of children to the adult world and retards their social development. Only later do they discover the larger world and its expectations regarding public behavior. Children don’t get as much exercise as they need, one cause of obesity among American children. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Carnival, 1997 |

Venice has relatively few gardens and parks, but the complete absence of cars makes it safe for children to play anywhere, even in the middle of the street. The entire city serves as their playground, and, as children grow, they can explore steadily more of it. Two children who want to play together can safely walk to each other's homes, even from a very young age. Younger children walk to school, and older children sometimes take the ferry.

Because all but the very youngest children can go to school on their own, without adult help, children begin very early to learn how to get along in the real world. If children on the street become obnoxious, a passing adult may correct their behavior, so children begin to absorb social norms from a young age. By the time they reach their teens, children have learned how to behave in public. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The first five stories are mostly parking garage |

Street LifeThe constant heavy traffic makes the streets noisy, smelly, and abidingly ugly. It is unpleasant and even difficult to socialize on the street, and few people do. What passes for street life takes place inside large, privately-owned shopping centers that have little incentive to permit or encourage activities that are not directly profit-making. Unlike city streets, malls close at night. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Better acoustics than some concert halls |

In Venice, cars never intrude upon the streets except for a small area near the parking garage at the entrance to the city. Rich and poor alike use the streets at every hour of the day and night. Long trips begin and end with a walk between the door and the nearest ferry landing. Water taxis are for hire at stiff rates, but even their passengers usually begin their trips with a walk down the street.

The streets echo to human sounds: footsteps, voices, whistling porters, singing gondoliers. The stink, roar, and danger of car and truck traffic never inhibit street life. People dawdle without worrying about onrushing traffic. All day long, people are present on the street, which serves as a stage for an endless stream of interesting and sometimes amusing episodes. Restaurants put tables outdoors, from which their patrons watch and participate in the play of life. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Public SpacesBeauty and the needs of pedestrians are given little thought, and the long strips of low buildings bordering wide streets fail to create a sense of enclosure. Comfortable places where people gather to enjoy city life scarcely exist. Attractive public squares can hardly be found. Graffiti and litter abound in an environment about which no one cares. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In Venice, public squares large and small are scattered throughout the city. These squares were arranged for the sole convenience of pedestrians, many of whom are intimately familiar with the area, so few signs are required. In Venice, the church acted as a major organizational force, and each parish has its own church, usually fronting on a square that once served as a water catchment and storage area, furnished with a well from which people drew their water. While drawing water is no longer an activity that regulates daily life, the wellheads remain gathering places, and people cluster around them to enjoy the vibrant street life. Building facades almost entirely delineate these squares, giving them an interesting and comfortable sense of enclosure. A few squares, including the great Piazza San Marco, border on the lagoon, with its arresting water views. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Major StreetsThe street is no place to stop to look around or to chat with neighbors. Should a motorist stop for any reason, drivers would begin honking their horns almost immediately. Giant signs and power lines blot the scene. No thought has been given to the provision of any amenity except parking. The street fails to serve as a social space. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In Venice, people sometimes nearly fill a street, but real congestion is rare. In this photograph of one of the busiest spots in Venice, many more people are present than in the photograph of Los Angeles. There is room enough for everyone, even though the way is partially blocked by a few people sitting on the steps. The businesses face directly onto the sidewalk and have no need to shout in order to advertise their wares. As in most of Europe, the high density made it practical to put power lines underground. None of the people are isolated in steel cages, so everyone is actively present on the street. Many stores have no signs at all. Restaurants put their menu cards out on small stands, and the tables in the street are sufficient to announce the nature of the business to passersby. The street is attractive and serves as an active social area. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

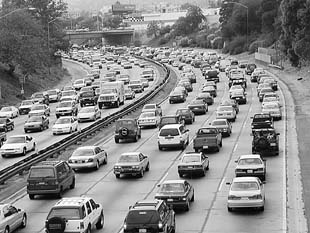

Passenger TransportAir pollution remains a serious issue as traffic continues to worsen. People waste large amounts of time stuck in traffic. Those without a car must endure dreadful bus service in order to get anywhere. Those who drive spend a large proportion of their disposable income for relatively low-speed transport, which is, of course, faster than the bus. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

In Venice, walking is the most common way to get around, and congestion is rarely an issue. At a reasonably brisk pace, one can cross the city in an hour. Pleasant, if slow, public transport is provided by ferryboats, but evening service is infrequent, and it is often faster to walk. (The gondola is little used as a serious means of transport today.) Those arriving by car must park in a large garage at the end of the causeway. A small area near the garage is the only part of the city in which cars, trucks, buses, or trains can be found. The atmosphere aboard the ferries is pleasant, and passengers enjoy excellent views of the city. Arched bridges, necessary to allow boats to pass beneath, abound in Venice. These bridges all have steps, making this one of the world’s least accessible cities for those confined to wheelchairs. Lifts are now being added to the most heavily traveled bridges. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Freight DeliveryThe use of trucks to deliver so much freight aggravates the already-severe road congestion. Most big trucks are diesel-powered and emit clouds of stinking exhaust, and all trucks exacerbate global warming because they burn fossil fuels and waste energy. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In Venice, virtually all freight is transported by boat, except for a small area near the train station that has direct rail and road service. The narrow waterways and low bridges restrict the size of freight scows, so their capacity is quite limited. Freight must be transshipped between rail or road and the delivery boats, a time-consuming and expensive task. Final deliveries, except to destinations along a canal, must be made by hand cart. The steps on the bridges make this a chore for the very fit, and it is doubtless a bit dangerous as well. Despite these problems, freight gets delivered in Venice, and even the overnight express companies have managed to cope. Street and water traffic never interfere with one another, and congestion on the water rarely becomes an issue. While the diesel-powered boats do emit some pollutants, they are reasonably quiet and rarely intrusive. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Civic BuildingsThe problem of car parking is insoluble. While multistory parking garages do reduce the amount of land required, they are never attractive structures. As long as the car remains the primary means of access, the design of beautiful public buildings in attractive surroundings will remain an impossible task. Despite its importance, this building could quite easily be mistaken for an ordinary office building. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In Venice, the Doge’s Palace is clearly the most important civic building. No one arrives by car, so there is, of course, no car parking at all. One facade faces the Riva degli Schiavone, a busy waterfront where a variety of boats moor. This is as close to a parking lot as exists anywhere in the vicinity. The moored and moving boats, rather than detracting from the appearance and habitability of the area, actually make it more interesting. While the monumental architecture of the Doge’s Palace is best appreciated from other vantage points, even here on the back side, one sees the attention paid to making the building beautiful. The principal facade of the Doge’s Palace faces the Piazza San Marco where it and the adjoining cathedral form the grandest architectural feature of the piazza, and thus of all Venice. The importance of this building is unmistakable from any prospect. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

ChurchesMost of what is visible from the street is parking lot. In this instance, a few token trees were added to shield the expanse of sizzling asphalt and the mass of parked cars, but the entire arrangement inspires awe only by the breadth and depth of its ugliness. Only the cross marks this site as different from any other. The building itself is in no way remarkable (this one was probably converted from a failed store). The fence and the gate imply that only some people are welcome, and this church provides no amenities whatever to passersby. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In Venice, those going to church begin to meet each other in the streets during their walk to church. The social function thus begins well before their arrival at the church itself. Since everyone walks to church, there is no need to make any provision for parking. The street is narrow enough that the cost of stone paving was reasonable. This church faces directly onto the street. The rich architectural details are seen from close up and intended to be appreciated by passersby as a sign that this building is important enough to be worthy of decoration. (By Venetian standards, this church is only barely worthy of note.) Great care was lavished on the design and execution of the lovely stone paving. This particular church is generous enough to provide a pleasant amenity to the general public: a sunny place to sit and watch the world go past. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

HousingA large percentage of almost every building site must be devoted to parking and access roads, leaving little room for public spaces. The ground floor may be dedicated entirely to garages, as here, so there is often no human presence at ground level, which makes the area hostile, forbidding, and even frightening. Few architectural elements can be more difficult to make beautiful than garage doors, and most housing is overwhelmed by these faceless artifacts of automobility, which foil every effort to design attractive buildings. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

All residential buildings in Venice were designed with the assumption that everyone would arrive either on foot or by boat. No provision need be made for parking lots or garages. Most buildings that front on a canal are provided with landing stages for boats, although almost everybody makes all local trips on foot. Absent the need for car parking, open space is invariably devoted to human uses. It is true that open space is scarce in the older parts of Venice, and much of this takes the form of private gardens. Parks are few and small, but the high quality of public spaces and the omnipresent water views offer a delightful alternative. The surroundings are never threatening. In the absence of the need for garages, the design of attractive buildings is a relatively straightforward matter, even here, where the style here has been kept rather simple. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

ShoppingBecause customers and store employees come from a wide geographic area, they seldom know or even recognize each other and rarely have any social contact outside the store. Should a customer burst into tears, no one would know why. The store is owned by a distant corporation and managed from afar. The business knows its customers only by their demographic profiles but does its best to accommodate them, for its livelihood depends upon it. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In Venice, small buildings house small enterprises from which a few people, or a family, serve a small geographic area. Transport is by foot, and the surroundings are always agreeable. These businesses may have located at their current address generations ago. The people who work and shop in these stores know each other, sometimes quite well. Both customers and staff usually live within the same neighborhood, so sometimes they meet on the street. They know the local gossip and the recent misfortunes. A customer who is recently bereaved can expect to be greeted with compassion when entering the store for the first time since the death. The proprietor is present during opening hours. He has learned the special needs and desires of all his customers and does his best to accommodate them, for his livelihood depends upon it. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Los Angeles is the archetype of the auto-centric city and so was chosen as the first element in this comparison. Venice, the only large existing carfree city, was chosen as the second element. The final element is a hypothetical carfree city based on the reference design presented in Part II of this work. |

The Alpha & OmegaThis table compares Los Angeles, Venice, and the carfree city as proposed in Part II. More stars indicate better conditions. Judgements are, of course, subjective. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On statistical quality-of-life measures, Venice ought to fare as well as any city in the developed nations. For administrative purposes, the mainland near Venice is part of Venice, but I have omitted the mainland (with its auto-centric patterns) from this comparison. I have assumed that the car is used for all travel in Los Angeles; this reasonably approximates the current reality. Venice scores poorly on transport because the ferries provide relatively slow and infrequent service and because the use of motorboats to provide private transport and freight service results in some noise, pollution, and wake damage to buildings. New carfree cities will enjoy better passenger and freight transport than either Los Angeles or Venice.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Back to Book Home

Go to Carfree.com

carfree.com

Copyright ©2000-2002 J. Crawford, except

Photographs of Los Angeles Copyright ©1999 Richard Risemberg, except

Photograph of Los Angeles City Hall Copyright ©1999 Jack Risemberg